Lieutenant Colonel Peter Moore, who operated with the Partisans in Bosnia and Slovenia, describes the situation he experienced when he landed in Yugoslavia:

“I was dropped into the Yugoslav partisans. My first impression was one of surprise at the way the charcoal gas truck, which took us on our way to Jajce moved openly in broad daylight along the road, leaving a plume of dust for many hundreds of metres behind it. Although we stood ready to bale out at the sound of a hostile aircraft, it was clear that the partisans had a firm grip on the countryside in the liberated areas and that the air surveillance effort must have been limited. By this time the partisans moved relatively freely on the roads and had day-to-day control of considerable areas. They wisely did not attempt to stop incursions by armoured columns but melted away into the woods to strike elsewhere, at the exposed enemy’s communications. It was beyond the German’s resources to maintain themselves in such areas.”

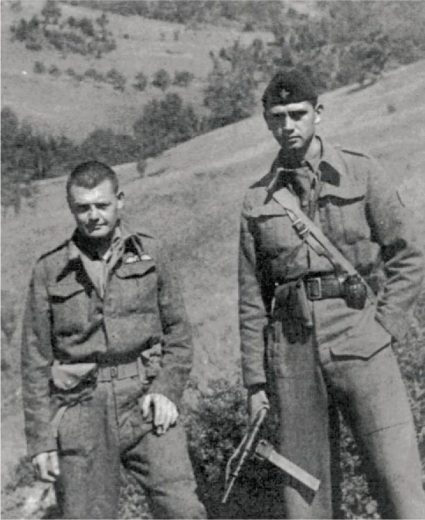

Captain Edgar Hargreaves described his arrival in Serbia:

“They were very friendly indeed – lots of kissing. They’re very emotional and they grasped you in their arms. They were all rather spectacular looking – I think quite a large number of them had made an oath not to cut their hair or shave until the country was liberated. They’d been living in the woods for rather a long time and they looked rather spectacular. They had a form of national dress which most of them were wearing – it was really a uniform. They had these things called ‘shubaras’ – funny woollen hats rather like the Cossacks used to wear and were draped with three rounds of bandoliers. They were not very fully armed and it was all very primitive.”

By the time that the Red Army arrived, some 12,000 Partisan wounded had been evacuated by air to Italy.

Vladimir Dedijer, Tito’s biographer, described the impact:

“The taking of the wounded to Italy represented the greatest aid which we received from the Allies during the war. This not only meant the saving of the lives of our wounded comrades, but also the unburdening of our units, which in this way became far more mobile. They did not have to give up comrades to carry the wounded, to guard them, but could now manoeuvre freely.”

Maj Basil Davidson went on to describe it from a British perspective:

“Partisan warfare was very fluid and mobile and you had to move from A to B very fast and you can’t move from A to B if you have to carry with you hundreds and hundreds of wounded men and women. So the only way you could handle the thing was either to risk their being executed by the Germans or to evacuate them by air. And I’m very proud to say, and I think all of us are very proud to remember, that we did evacuate many hundreds of wounded, wounded from the area where I was, which was far inland within sight and sound of Belgrade where there were three German divisions. And that got rid of the wounded, because the wounded, if they were found by the Germans would invariably shot, with their nurses and with their doctors. They were shot out of hand.”